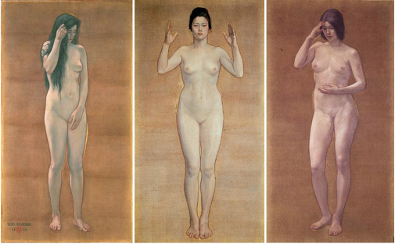

A “renowned” artwork that is often addressed by art critics to discuss the relationship between female identity and Japanese art is the 1897 oil painting Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment by Kuroda Seiki.[1] In this painting, three nude female figures are depicted against an empty background with such refinement that they resemble an animal specimen. Bijin-ga[2], the genre to which the painting belongs, illustrates how women’s bodies, not just in paintings but also in real life, are subject to the gaze of men.[3] This paper disrupts the traditional male narrative about female bodies through an analysis of the kawaii mascot Manko-Chan by Rokudenashiko. In the first part, it relies on English and Chinese translations of Japanese sources as well as commentaries by Anglo-American scholars to provide a background into the feminist dialogue in Japan and discussions surrounding Rokudenashiko. Secondly, it analyzes Manko-Chan in light of Clement Greenburg’s concept of kitsch and addresses gender contradictions through Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Ultimately, I argue that the notion of cuteness in Rokudenashiko’s work represents an act of defiance against the relegation of women as the inferior Other.

Although women, and women’s bodies in particular, have been a popular subject among Japanese artists since the Edo period (1603 – 1867), there is still a lack of recognition towards female artists, largely due to the historical dismissal of female artists by the mainstream Japanese art world.[4] During the last decade, however, curators, art historians and critics have made an effort to recognize the talent of women artists. This shift was signaled by the “gender debate” in 1997 in which famous feminist artists, such as Chino Kaori, participated.[5] In one of her speeches, Kaori accuses the art history establishment of its inherently partial and biased scholarship.[6] This accusation triggered what curator Mitsuda Yuri called an “allergic response” among art historians.[7] Some of the symptoms of this “allergy” include statements like “I felt offended in a way that words can’t describe… I don’t know how far she wants to go…”[8] Conservative art historians discredited Yuri by saying that “gender” can itself be “an unconditional correctness that oppresses the art,”[9] while defenders of feminism dismissed such objections as “little more than a defensive reaction of a critic whose masculinist privilege was threatened.”[10] Within this debate, Reiko Kokatsu pointed out that feminist art no longer deals exclusively with the binary of female-male, but “extends its perspective to value the various minorities with regard to … body and sexuality.”[11] Despite the artists’ assertions, the debate did not have much influence on the mainstream public’s response to male and female opposition, as Japan continued to rely on its traditional “phallocentric society” which is rooted in the authority of patriarchal economy and a clear gender division between masculine and feminine.[12]

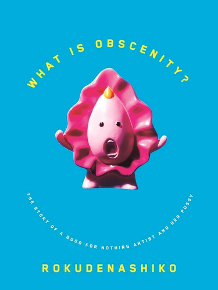

In recent years, one contemporary feminist artist who has challenged the male-oriented ethos of Japanese society and enjoyed great attention from Japanese journalists is Megumi Ishigari, who works under the pseudonym, Rokudenashiko (literally translates into Good-for-nothing-girl). She has created many objects based on a 3-D image of her own vagina, including a kayak, that led to her first arrest in 2014 and 20,000 signatures demanding her release. It was this arrest that received large media coverage and introduced her work to a younger generation of Japanese audiences.[13] Based on this experience, she published a manga titled What is Obscenity? The Story of a Good for Nothing Artist and Her Pussy, which features the character Manko-chan. The character has been reproduced onto various products, including phone cases and stuffed dolls. Due to the fact that her works are mostly in the form of manga, or commodified, Rokudenashiko’s works are not regarded as high art and have barely received recognition among high art critics.[14]

The charge for which she was arrested, distributing obscene materials, has been widely debated by journalists since she was the first person to be arrested under such a charge in 40 years.[15] Censorship against genitalia has existed in Japan since the Edo period, which saw the condemnation of erotic art known as shunga, or “spring pictures,” by Tokugawa shogunate.[16] Whereas the legal concept of obscenity was deployed originally to restrict depiction of certain acts in words or images, nowadays, women’s genitalia in particular are still labeled as obscene. Rokudenashiko’s works aim to counter this cultural norm by making women’s genitalia “normal”.

However, ironically, since her arrest in 2014 till now, most of the scholarly conversation has centered on whether Rokudenashiko’s work should be categorized as obscenity. In his discussion of artistic expression, critic Mark J.McLelland compares her art to shunga with the standard of whether her art may “deprive and corrupt” the minds of the viewer.[17] A majority of responses also have focused on the media effect of Rokudenashiko’s arrest, highlighted the fine line between obscenity and art in court, and puzzled over Rokudenashiko’s unprecedented refusal to confess.[18] For Ann McKnight, the media’s response is connected to the artist’s intrepid style: the pop tone of her art, the perceived vulgarity of the subject matter, and its mass production, all which enable a connection between her ideas and common Japanese citizen’s experiences.[19] Only a small number of scholars point to the fact that Rokudenashiko’s art resembles a “weird contradiction” towards sexuality.[20] In other words, most scholarly critics have chosen to ignore Rokudenashiko’s challenge to phallocentrism and become distracted by the media controversies instead of focusing on her work.

Furthermore, although recognized as political, Rokudenashiko’s art is barely included in conversations about feminism in Japan. Yet the contemporary nature of her work may provide important insight on the shifting gender dynamics in current Japanese society. Through an analysis of her rarely analyzed character Manko-chan, this paper addresses the neglect of Rokudenashiko’s art in Japan’s gender debate today.

Kitsch and The Other

In the manga What Is Obscenity? The Story of a Good for Nothing Artist and Her Pussy, Manko-chan appears in chapter six of the author’s autobiography and becomes the first-person in the last chapter titled This Is My Story.[21] The last chapter is also the only chapter in color, while the rest of the manga is sketched on a classic black-and-white panel. With its mouth wide open as if shouting, Manko-chan seems to be protesting something or appealing to its audience. Its exaggerated head-to-body ratio makes it appear like a child. From looking at its face circled by pink lace without knowing the artist who created it, one would never know that the inspiration of Manko-chan came from a vagina.

The fact that Manko-chan was inspired by Rokudanashiko’s identity as a woman and that her explicit statements about women’s genitalia have aroused so much controversy surely earns the work a place in the broader conversation about feminism.[22] In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag raises the question “Why should they (the war pictures) seek our gaze? What would they have to say to us? ‘We’ — this ‘we’ is everyone who has never experienced anything like what they (the soldiers) went through — don’t understand. We don’t get it. We truly can’t imagine what it was like.”[23] This question should be asked by all audiences when approaching a documentary of any creator’s own experience, regardless of the form of such documentary. The “pain” that Sontag discusses is not limited to physical pain in wars, but also the internal scars, such as those carried by women who have been victims of the male gaze. In relation to Mank-chan, the “we” refers to men, and Rokudenashiko’s work can be situated in the dialogue of male-female opposition.

The male-female opposition is discussed in Simone de Beauvoir’s book The Second Sex, in which she contextualizes it in the contradiction between the One and the Other. In her words, “alterity is the fundamental category of human thought. No group ever defines itself as One without immediately setting up the Other opposite itself.”[24] Distinguishing the Other from the One is a natural part of our process of understanding the world. This means that the otherness between women and men should not, by its nature, be associated with negative connotations. Yet, the otherness of women has been assigned a sense of inferiority. During the creation of modern Japan, women were ascribed the role of “good wives and wise mothers,” responsible for reproduction and socialization of children and being “passive supporters” of the “strong army,” made up of males.[25] Even after the Edo period during which Japan was largely influenced by western ideologies, after the 1997 gender debate (during a time when feminist ideas became heard), and after contraceptives gave women more active roles in the family, women were still identified as the inferior other.[26] As de Beauvoir has said, when a man has a reciprocal relationship with a woman, he will follow his ‘principle of abstract equality.’ However, when his interest clashes with hers, he will “apply the concrete inequality theme.”[27] The oppression allows a sense of superiority for the oppressor.[28] In the 1990s, women who rose to executive positions were called oyaji-gyrau (translates into “girls acting like a middle-aged man”).[29] According to Yumiko, this naming has a double function in that it uses the phallocentric narrative to degrade women and serves as a moral teaching to women about the “inappropriateness of their presence” in the workplace.[30] In this framework, men need to establish themselves as the authentic “One” and exclude the feminine as a degraded inauthentic “Other.”

Rokudeashiko targets this contradiction, especially the difference in responses to female versus male genitalia. She has mentioned in her manga that, while Japanese celebrate the Shinto festival Kanamara Matsuri (or the “festival of the Steel Phallus”), female genitalia are often termed with disgrace.[31] Even saying the word “manko“ (which is the Japanese equivalent of “pussy”) creates a nasty image.[32] After she was arrested for obscenity, media coverage about the arrest referred to Rokudenashiko as a “so-called artist,” excluding her from the realm of “high art.”[33] These are examples of the privileged “authentic” man’s “defensive responses” triggered by Rokudenashiko’s challenge of the authentic phallocentric narrative. The character Manko-chan is already a representative of rebellious acts under the authentic narrative; its shape is meant to resemble that of a vagina, and its story is based on Rokudenashiko’s arrest and subsequent defiance of the court’s ruling. In claiming her own female identity openly and publicly, even in the face of male opposition, Rokudenashiko poses a threat to the fortified and stable ego boundaries of Japanese men. Her self-representation through artwork allows her to position herself at “the margin of the phallocentric economy.”[34] Moreover, since she couldn’t find a legitimate place in the master narrative, she only appears as one of the “destabilizing elements.”[35] I contend that Manko-chan resolves such a contradiction, precisely by symbolizing the “destabilizing element,” which embodies the moral condemnation and shaming from those who feel threatened by the erosion of authority.

The embodiment is achieved through the artistic expression. The exaggerated body proportion of the character, its delightful pink color, and its soft texture all give rise to a sense of cuteness. In Japan, such an expression of cuteness is called Kawaii, closely linked to the notion of kawaiso, or “pitiful.”[36] The term is derived from pity and empathy towards small helpless creatures, for example children, and thus the aesthetics is highly related to the child figure as the epitome of vulnerability and innocence.[37] The rough sketches of manko-chan in the manga What is Obscenity also reminds readers of the illicit drawings of a child. On the one hand, the cuteness triggers an urge to protect; on the other hand, it can translate into a sense of weakness and passivity, which aligns with the male master narrative of inferior women. At the same time, Manko-chan is characterized with an explicit sense of resistance. This can be shown, not only by the fact that its inspiration comes from vagina, but also by its wide-open mouth and waving hand as if venting its anger against the overwhelming stereotype and prejudice against women. The rough sketches may appear childish, but they are also transgressive.

To advance her feminist agenda in the public sphere, Rokudenashiko has commercialized the character, producing various products and even creating a fan base. She has worked against the deep-entrenched male-female opposition by packing Manko-chan into a kitsch. In Takashi Murakami’s essay Superflat Manifesto, he claims that Superflat art is saturated with the “techno-aesthetics of Japanese anime in particular and mass-cultural engines in general.”[38] Similarly, Rokudenashiko‘s genre of work, manga, is also highly pop and mass-culture-based. Like Superflat, Manko-chan should fall under a branch of kitsch that is rooted in Japanese culture. The concept of kitsch was developed by Clement Greensburg as a “popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, etc.”[39] The prerequisite for kitsch includes the availability of a “fully matured cultural tradition, whose discoveries, acquisitions, and perfected self-consciousness kitsch can take advantage for its own ends.”[40] Manko-chan tacitly antagonizes the cultural tradition that positions women as the inferior other. Rokudenashiko borrows from the cultural “reservoir of accumulated experience” her themes — the resolution of women-men contradiction — and “converts them into a system” — which is her manga.[41]

Moreover, according to Greensburg, kitsch erases the distinction made between the values only to be found in art and those that could be found elsewhere.[42] This is because kitsch, as a form of art, depicts the effect of art; while high art expects audiences to reflect and react sensitively to its qualities, kitsch allows for vicarious experiences with “far greater immediacy” than high art.[43] For Manko-chan, which already embodies the pain of being confined to the margins, being a kitsch allows it to join the mainstream narrative. However, it wasn’t the explicit reference to female genitalia and protest that truly gave voice to Manko-chan, but rather, its cuteness that works as a delicate kind of revolt to the male-female opposition.

The usage of cuteness can also be found in another Japanese artist Nara Yoshimoto.[44] However, in his artwork, children, although also depicted with one-to-one head-body ratios to evoke cuteness, are full of anger and abjectness.[45] His works are a perfect example of how cuteness can be understood from another perspective that gives the character a completely different power. At first glance, the cuteness of Manko-chan, a kitsch, should attract a large segment of the population, called Otaku in Japanese. The stereotypical Otaku figures display high intimacy with mass-mediated objects, characterized as “a highly developed connoisseurship of animated minutiae.”[46] The Otaku figures are also associated with men possessing an “abnormal interest in manga, anime and electronic games featuring bishou-jo [translated as beautiful young woman].”[47] In other words, Manga-Chan first appeals to the group of people that consume the most of the merchandise that commodifies and exploits women’s bodies. Thus, Mango-Chan surreptitiously enters the master narrative and joins the “One.” However, being a representation of the experience of a marginalized person, Manko-chan is also a condemnation of the oppression enacted by the “One.” The kawaii character embodies the powerlessness of the “Other” who, in fact, has the power to turn into the opposite, a resistant testimony to the violence of domination. The cute object is “the most objectified of objects,” but it is precisely “the extremity of that objectification … the fundament of the potential resistance of cuteness.”[48] Moreover, it is crucial for cuteness to be a diminutive object that confronts the imposition of the “One.” That is, “it bears the look of an object not only formed but all too easily de-formed under the pressure of the subject’s feeling or attitude towards it.”[49] In other words, in one way, we can say that “the One” establishes the “Other;” but in another way, the “One” wouldn’t be the “One” without the presence of the “Other.” Manko-chan can fall under the master narrative due to its resemblance to the objectified “Others.” At the same time, it serves as a revolt because it subverts the master narrative from the inside out. It conveys that even though the “One” has control over the “Other,” the power of the “One” cannot exist without the “Other.”

Then, what solution does Rokudenashiko offer by her character Manko-chan? Manko-chan falls under the stereotypical passive figure that the “One” has assigned to the “Other,” but nonetheless manages to subvert the phallocentric narrative. In Japan, young women are often called shojo, a word that characterizes an amalgamation of youth, femininity, innocence, budding sexuality, but also a sense of autonomy.[50] The concept of shojo was first created by the Meiji government to educate girls under the slogan of “good wife and wise mother.”[51] A similarity between shojo and the aesthetics of kawaii is that they are both considered cute. Yet, while the idea of shojo may appear hyper-feminine, oppressive, and prejudicial, women at that time took advantage of shojo to become educated.[52] Moreover, over time, the core attribute of shojo—chastity—has become an emphasis on asexuality. According to Treat, shojo constitutes their own gender, “something importantly detached from the productive economy of heterosexual reproduction.”[53] Therefore, the concept of shojo is no longer an idealized frame and an inferior symbol imposed on women; it has become a possibility that can be embraced and manipulated by women themselves. In other words, what Rokudenashiko accomplishes through her work tells women that claiming their female identities and displaying of emphasized femininity can be an active and dynamic way for Japanese women to actually take control of their sexuality.

Conclusion

Unlike the women in Wisdom, Impression and Sentiment mentioned in the very beginning, Rokudenashiko is already claiming her body as her own property. While the oil painting is created from the male perspective and for the male gaze, Rokudenashiko has demonstrated how women’s bodies can be meaningful beyond ways that are conventionally sexualized and exploited in the phallocentric Japanese economy. The beautiful woman used to be a tangible expression for a hedonic promise made by the empire, a dehumanized symbol at the service of a society dominated by men. Now, the beautiful woman is a challenge to the stereotyped image of Japanese women.

Manko-chan has always been a representation of the “Other.” But instead of the inferior submissive “Other,” it characterizes a strong and independent “Other.” I would argue that what Mank-chan is trying to achieve is true reciprocity between the “One” and the “Other,” a symmetrical gender relationship devoid of any negative connotation. Many male audiences in Japan have accused Rokudenashiko’s work for being pornographical, but the vaginal reference is merely a tool to lure consumers of women’s bodies to confront women’s condemnation. Rokudenashiko’s use of her own body in such an “intentionally provocative, simplified and fictional” way transcends the presentation of genitals and other fetishized body elements.[54] Using the tool of kawai assigned to women, she is already taking a step out of the “margin” to “destabilize” the phallocentric narrative.

Footnotes

[1] For more analysis see Joan Kee, “Modern Art in Late Colonial Korea: A Research Experiment,” Modernism 25, no.2 (2018): 220. Although the focus of this article is not Japanese art, when discussing about the relationship between women body and art, Kee specifically addressed this painting. In her words, such artistic representations of beautiful women serve for the men as a vision free of sweat, dirt and pain, and thus provide “tangible expression of the promises made by a burgeoning empire.”

[2] Bijin-ga is a genre of painting in Japan depicting beautiful women, “emerging in rhetorical response to various political and social imperatives.” In other words, bijin-ga is created for the public display, often socially recognized as personal enjoyment.

[3] Katõ Ruiko, “Bijin-ga”, in Nihonga: Transcending the Past, trans. Reiko Tomii (Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 1996), 108 – 109.

[4] Midori Yoshimoto, “Women artists in the Japanese Postwar Avant-Garde: Celebrating a Multiplicity,” Women’s Art Journal 27, no. 1 (2006): 26.

[5] “Gender debate” (jendã ronsõ): In the article on feminist art history, Ayako explained that the word “gender” can be used differently in Japanese culture: feminists use it to challenge discrimination based on gender differences; non-feminists use it as an alternative to “feminism” and “women’s liberation”; and anti-feminists use it to highlight “natural” gender differences. For a comprehensive explanation, see Ayako Kano, “Women? Japan? Art?: Chino Kaori and the Feminist Art History Debates,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 15, Japanese Art: The Scholarship and Legacy of Chino Kaori (2003): 25-38.

[6] Kano, “Women? Japan? Art?,” 26.

[7] Mitsuda Yuri, “Gender Studies and Allergies,” in Women? Japan? Beauty? (Tokyo, Shoto Museum, 1996), 155 – 56

[8] Kano Hiroyuki, “The Edo Period is the Edo Period,” Art Forum 21, no. 1 (1999): 117.

[9] Sanda Haruo, “Thoughts on Situation 6: On Borrowed Thought, Knowledge, ad Themes,” LR, no.3 (1997): 25.

[10] Kano, “Women? Japan? Art?,” 32.

[11] Kokatsu Reiko, “Responding Again to Mr. Sanda Concerning the Logic of Oppression: Another Look at Gender and Art,” LR, no.8 (1998): 70-76.

[12] Yumiko IIDA, “Beyond the ’Feminization of Masculinity’: Transforming Patriarchy with the ’Feminine’ in Contemporary Japanese Youth Culture,” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6, no.1 (2015): 2.

[13] Ishigari Megumi, What is Obscenity? The Story of a Good for Nothing Artist and Her Pussy, tans. Anne Ishii (Toronto, Koyama Press, 2016), 25.

[14] Out of all the works that I have researched online, only three approached Rokudenashiko’s work by looking at her artistic expression.

[15] Megumi, What is Obscenity?, 54.

[16] Mark J.McLelland, “Art as Activism in Japan: The Case of a Good-for-Nothing Kid and Her Pussy,” (master’s thesis, University of Wollongong Australia, 2018), 4.

[17] J.McLelland, ”Art as Activism in Japan,” 4.

[18] Over 99% of criminal trials in Japan end in conviction, a staggering figure compared to other countries with judicial court systems (in the US, the rate of conviction is around 85%). Some in both the international and domestic human rights community have blamed bureaucratic nepotism and the National Police’s penchant for forcing confessions or plea bargaining for the unusually high conviction rate. Although the rate of conviction is high, the rate of prosecution is comparatively low, since many offenses are dismissed dur to” lack of immediate threat,” public outcry, or uncooperative plaintiffs. The fact that Rokudenashiko has refused to plea bargain and has campaigned for public support which she has won), then, is historically extraordinary for the Japanese criminal justice system. More information see Megumi, “What is Obscenity,” 54.

[19] Anne McKnight, “Obscenity and Modularity in Rokudenashiko’s Media Response,” FIELD no.8 (2017): 6.

[20] According to Annemarie Luck, in Japan, people from all ages consume manga that exploits sex, but are publicly shamed for “owning their own sexuality;” Japanese consumers adore kawaii culture that features childish and cute characters, but kawaii are also used to depict fantasies related to obscenity. More explanation see Annemarie Luck, “Japan’s Madonna Complex,” Index on Censorship 46, no.1 (2017): 3.

[21] Megumi, What is Obscenity, 167-176.

[22] Rokudenashiko has claimed herself as a feminist artist. See Megumi, What is Obscenity?, 113.

[23] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Picador, 2003), 97.

[24] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 26

[25] Vera Mackie, “Introduction,” Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003),3

[26] Sumiko Iwao, “Maternal Bonds,” Japanese Women, (New York: The Free Press, 1993).

[27] de Beauvoir, The Second Sex, 34-35.

[28] Simone de Beauvoir, The Second, Sex, 33

[29] Yumikon, “Beyond the ’Feminization of Masculinity,” 64.

[30] Beyond the “Feminization of Masculinity,” 63.

[31] Megumi, What is Obscenity?, 113.

[32] Megumi, What is Obscenity?, 113.

[33] Megumi, What is Obscenity?, 112.

[34] IIDA, “Beyond the ’Feminization of Masculinity,” 13.

[35] IIDA, “Beyond the ’Feminization of Masculinity,” 13.

[36] Marilyn Ivy, “The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo’s Parapolitics,” Mechademia 5, (2010): 13.

[37] Ivy, “The Art of Cute Little Things,” 13.

[38] Superflat is a postmodern art movement, founded by the artist Takashi Murakami, which is influenced by manga and anime.

Anime is hand-drawn or computer-generated anime originating first from manga. In other words, anime is the animated manga.

More explanation on Superflat see Takashi Murakami, “A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art,” Super Flat (Tokyo: Madra, 2008): 25.

[39] Clement Greenburg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Art and Culture (Massachusetts: Beacon Press, 1961): 5.

[40] Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” 5.

[41] Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” 6.

[42] Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” 7.

[43] Greenberg, “Avant-garde and Kitsch,” 7. Here Greenberg referred Picasso’s painting as “cause” since it requires the “reflected” effect, while Repin has already included the “reflected” effect in his painting.

[44] Ivy, “The Art of Cute Little Things,” 3.

[45] Ivy, “The Art of Cute Little Things,” 5.

[46] Ivy, “The Art of Cute Little Things,” 2.

[47] Patrick W. Galbraith, Routledge handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia, ed. Mark McLelland and Vera Mackie (New York: Routledge, 2015): 13. Bishou-jo is a Japanese term that literally translates into beautiful young women.

[48] Sianne Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” Critical Inquiry 31, no.4 (2017), 814.

[49] Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant Garde,” 816-817.

[50] Masafumi Monden, ”Being Alice in Japan: Performing a Cute, ’Girlish’ Revolt,” Japan Forum 26, issue 2 (2014): 226.

[51] Monden, “Being Alice in Japan,” 9.

[52] Monden, “Being Alice in Japan,” 10.

[53] John Whittier Treat, “Yoshimoto Banana Writes Home: Shojo Culture and the Nostalgic Subject,” Journal of Japanese Studies 19, no.2 (1993), 353-387.

[54] McKnight, “Obscenity and Modularity in Rokudenashiko’s Media Activism,” 3.

Bibliography

Greenburg, Clement. “Avant-Garde and Kitsch.” Art and Culture. Massachusetts: Beacon Press,1961.

Haruo, Sanda. “Thoughts on Situation 6: On Borrowed Thought, Knowledge, ad Themes.” LR, no.3 (1997):25.

Hiroyuki, Kano. “The Edo Period is the Edo Period.” Art Forum 21, no. 1 (1999): 117.

IIDA, Yumiko. “Beyond the ’Feminization of Masculinity’: Transforming Patriarchy with the

‘Feminine’ in Contemporary Japanese Youth Culture.” Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 6, no.1 (2015): 2.

Ivy, Marilyn. “The Art of Cute Little Things: Nara Yoshitomo’s Parapolitics.” Mechademia 5, (2010): 13.

Iwao, Sumiko. ”Maternal Bonds.” Japanese Women. New York: The Free Press, 1993.

J.McLelland, Mark. “Art as Activism in japan: The Case of a Good-for-Nothing Kid and Her Pussy.” Master’s thesis, University of Wollongong Australia, 2018. 4.

Kano, Ayako. “Women? Japan? Art?: Chino Kaori and the Feminist Art History Debates.” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 15, Japanese Art: The Scholarship and Legacy of Chino Kaori (2003): 25-38.

Kee, Joan. “Modern Art in Late Colonial Korea: A Research Experiment.” Modernism 25, no.2 (2018): 220.

Luck, Annemarie. “Japan’s Madonna Complex.” Index on Censorship 46, no.1 (2017): 3.

Mackie, Vera. “Introduction.” Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

McKnight, Anne. “Obscenity and Modularity in Rokudenashiko’s Media Response.” FIELD, no.8 (2017): 6.

Megumi, Ishigari. What is Obscenity? The Story of a Good for Nothing Artist and Her Pussy. Translated by Anne Ishii. Toronto: Koyama Press, 2016. 25.

Monden, Masafumi. “Being Alice in Japan: Performing a Cute, ’Girlish’ Revolt,” Japan Forum 26, issue 2 (2014): 226.

Murakami, Takashi. “A Theory of Super Flat Japanese Art.” Super Flat. Tokyo: Madra, 2008.

Ngai, Sianne. “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde.” Critical Inquiry 31, no.4 (2017): 814.

Reiko, Kokatsu. “Responding Again to Mr. Sanda Concerning the Logic of Oppression: Another Look at Gender and Art.” LR, no.8 (1998): 70-76.

Ruiko, Katõ. “Bijin-ga.” In Nihonga: Transcending the Past. Translated by Reiko Tomii. 108-109. Saint Louis: Saint Louis Art Museum, 1996.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador, 2003.W. Galbraith, Patrick. Routledge handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia, ed. Mark McLelland and Vera Mackie, 13. New York: Routledge, 2015.

Whittier Treat, John. “Yoshimoto Banana Writes Home: Shojo Culture and the Nostalgic Subject.” Journal of Japanese Studies 19, no.2 (1993): 353-387.

Yoshimoto, Midori. “Women artists in the Japanese Postwar Avant-Garde: Celebrating Multiplicity.”Women’s Art Journal 27, no. 1 (2006): 26.

Yuri, Mitsuda. “Gender Studies and Allergies.” in Women? Japan? Beauty? , 156-159. Tokyo, Shoto Museum, 1996.